Nobody wanted this. I was hoping for a bright start to this year. I was all ready to write an essay of optimism and cheer. On this Inauguration Eve, there should be promise coming – a new slate of vaccines, a change in leadership, an economic restart for the country. Instead, we’re watching a quickly unfolding story of security failures, political violence, and social polarization. 2021 could have been a fresh start, but it’s already a cautionary tale of how we’ve failed as a civil society.

Our country isn’t inviolable. It never has been. The failed Capitol coup isn’t a break in our reality, it’s a continuation of our history. But a revisionist approach to art history makes the sight of white violence unbelievable even in real time. Somehow the imagery of a white mob, attempting to destroy a government through brute force, still seems unimaginable to many Americans. That amazes me. White bodies dominate our national culture, whether in art, journalism, politics, finance, or other spheres. Our arts institutions cling to the cultural patrimony of European art, even while people of color have called to #DecolonizetheCanon for decades.

So if that’s our legacy, let’s get real about it. Our reflections of whiteness in art seem limited to heroic sculpture or gauzy pastoral landscapes. When our arts institutions curate or call in loans from European collections, it’s rarely about the failure of white nationalism or racism. The violent extremists that besieged our entire legislature took inspiration from the fascist movements of the last century – their appalling insignia, merch, and slogans make that clear. When arts institutions fail to wrestle with that legacy, it creates a predictable failure of imagination. The real trauma of the past is disappeared from our visual memory. We can’t reproduce or imagine how white nationalism creates a society shredding itself, patriotism lashing back against the people it pretends to protect. That’s our cultural heritage as well. For people of color, our survival depends on recognizing and deflecting white violence. But we aren’t the only Americans affected.

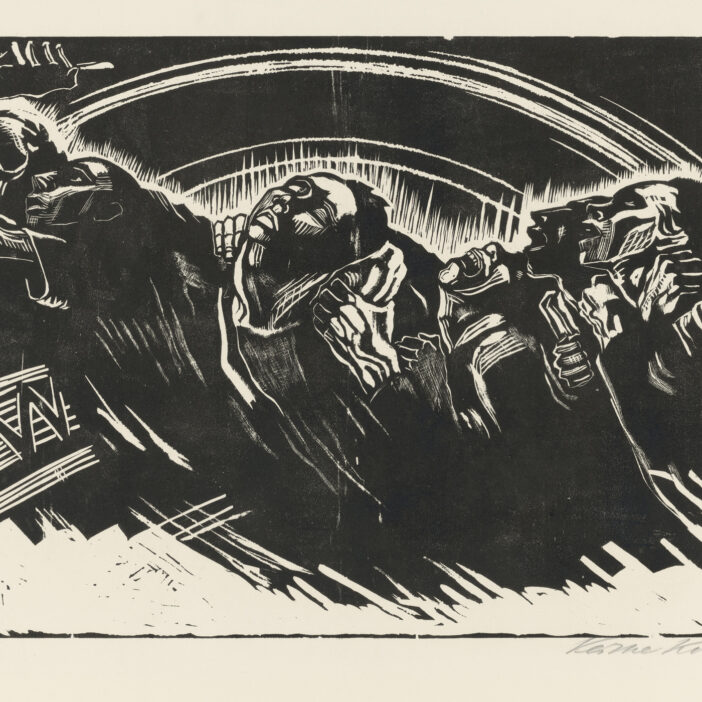

By forgetting the white artists who showed the cost of political violence, we do ourselves a disservice. German artist Käthe Kollwitz lost a son during the First World War, was harassed by the Nazi regime throughout the Third Reich, and died shortly before the end of the Second World War. Through it all, she testified to the pain of her times. She created work that showed European nationalism setting the world aflame, destroying families and drawing countries and continents into armed conflict. She shows white people suffering the effects of white nationalism. And we rarely see work like hers today. Poking around the internet, I found an article on Artnet about current opinions of her work. The TL:DR version is “she’s too emotional, too hard, and too intense.” True story – so is life.

The most surprising thing about the insurrection for me isn’t that is happened, it’s how quickly Americans are willing to turn away and move on. If there’s anything we can learn from Europe, through art history or otherwise, it’s that the fires of white nationalism don’t die out on their own. I’ll let Käthe close out the beginning of this month, and hope for better soon.

“They all devoted their lives to the idea of patriotism.

The young men in England, Russia and France did the same.

The result was […] an impoverished Europe robbed it of its most beautiful people. Was the youth in all these countries deceived?”

Käthe Kollwitz, Diaries, 11 October 1917

Image Credit: The Volunteers, sheet 2 of the series “War.” Woodcut, 1921/1922, courtesy of Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln. The museum calls this a “Danses Macabres” lead by a figure Death. Dancing to one’s death – a fitting image for a post-riot and mid-pandemic time. Let’s do better.

Spelling error updated August 3, 2021.